Dożynki is an annual harvest festival celebrated in Poland around the turn of August and September that dates back maybe even to the ancient times. To majority of acclaimed historic Polish folklorists, researchers, and poets, such as Oskar Kolberg, Zygmunt Gloger, Ignacy Krasicki, Józef Ignacy Kraszewski, and numerous others, it’s been more than clear that dożynki hold many remnants of a pre-Christian feast of fertility and crops, dedicated to gods of prolificacy, celebrated in rural communities over the centuries ever since the pagan times and eventually syncretized with Christianity.

You might’ve already heard about that festival under the name of dozhinki (how it is very often spelled in the English language). Remnants of that mysterious Slavic festival survived in all Slavic countries under many similar names in local forms of harvest festivities. In Poland it’s been known also under names of wyżynki, obżynki (these two along with the name of dożynki are related to the word żeniec – old Polish word for a reaper), okrężne (from okrężny – roundabout, coming from a custom of ritual encircling of the crop fields), wieńcowe, wieńczyny (from wieniec – wreath or garland), and other regional names that could also be used separately to describe certain parts or rituals performed during that festival.

Before I go into details, I recommend you first to read my older article describing the symbolism of bread, and the rituals of the season of harvest itself before continuing to read about dożynki which is the culminating point of that season.

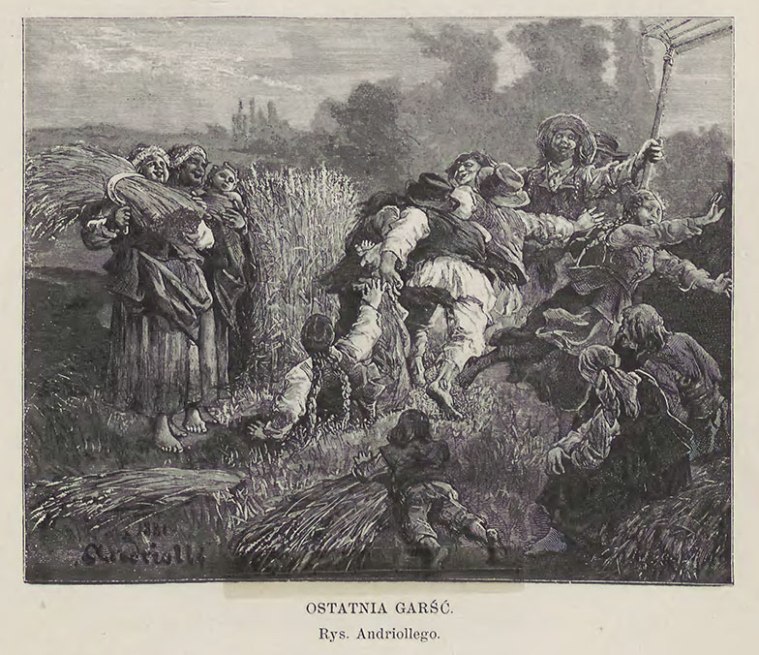

CUTTING OF THE LAST SHEAF OF GRAIN

Beginning of each dożynki was marked with the moment the last crops got harvested from the fields. Essentially, the first ritual that was considered a start of the celebrations was a ceremonial cutting of the last sheaf of grain from the fields.

Every year a small section of healthy-looking grain was left uncut on the fields by the harvesters in preparations for that ceremony. It was chosen in a visible section of the field, usually close to a road or a pathway, and it was decorated with flowers and green leaves, as if the community wanted to boast: our work here is done, the field is ready, we’re preparing for dożynki.

That section of grain had its own name, varying between regions, such as: wiązanka, garstka, równianka, plonkopka, przepiórka, popiórka, perepełka, koza, pępek. I find the last one the most significant: meaning literally a navel, it shows a peculiar symbolism the most clearly. It’s almost as if that ritual cherished the field as a mother’s womb, and the crops as the child she gave birth to – cutting off that “last sheaf” was celebrated almost like cutting off a newborn’s navel after a long process of confinement, and the process contained a lot of symbolism connected to fertility. It was a common belief that this “last sheaf” holds mysterious powers, decisive in the annual vegetative cycle of life.

The community rested for a day or a few days after the weeks-long season of harvest, and when everyone was ready for the festivities, they came back to the chosen field to perform a variety of rituals involving the “last sheaf”, differing in details between certain regions of Poland.

In regions such as Kurpie and Podlasie a certain custom called oborywanie przepiórki (ploughing of the “last sheaf”) survived up until the end of 19th century. It was a symbolic “ploughing” of the soil around the “last sheaf”, and it was done by dragging a young girl (often specified as a virgin) on the ground around the “last sheaf” that was decorated with flowers. That ritual meant to increase the fertility of the soil for the next harvest.

In the region of Wielkopolska people performed a ritual very similar in its nature. There, a local community chose two young people: a girl and a boy, who were rewarded for their hard work during the harvest. It was considered an honour to perform in the ritual. They laid down on the ground, and crawled in circle around the “last sheaf” before cutting it down.

The “last sheaf” was cut down in a ceremonial manner, usually by the owner of the farm or a respectable gospodarz / starosta in the community.

In all regions of Poland it was later used in creating a decorative garland for the festival.

Another popular custom was called okrężne (which I mentioned briefly at the beginning). It involved a ritual procession around the fields. In the old days it was done for three main reasons: to make sure the field was properly cleared, to designate the field borders for next harvest, and to protect it from natural disasters, from evil charms and spells and from the demons. Okrężne was performed twice a year, in spring when the fields were prepared for the new season, and then in late summer or early autumn around the time of dożynki.

MAKING OF CEREMONIAL GARLANDS

Artisans in the rural communities prepared a decorative wieniec (garland or wreath), incorporating the cut-down “last sheaf” from the fields into its construction. That was meant to ensure a good continuity of the harvest in the next year. The garland was decorated with flowers, grains, fruits, herbs – all the most important goods collected during the season of harvest.

The garlands have many regional forms and shapes, and can even take very sculptural forms (such as figures of the Holy Mother, the Polish Eagle, a crown, or other forms important at the time of creation by the community). They come in so many forms and sizes, I advise you to just search for “wieńce dożynkowe” and look at the pictures in case you’re curious.

The garlands often reach truly astonishing size, and are built around a supportive construction made from wood or metal that allows to create bigger-sized sculptures. They could reach the height of around 3 meters (9.8 feet). The most desired height would be often around 2 meters (6.5 feet), above the average height of a man. It’s due to an ancient custom that comes from the pre-Christian times.

Although already forgotten over the long centuries, size of the garland might’ve been determined by a custom as following: a Slavic elder stood behind a huge bread made from fresh crops, and asked people if they could still see him above its height – therefore wishing for a better harvest in the next year, so that the next time the community wouldn’t be able to see him at all from behind the huge amount of the stacked food. That ceremony was apparently very important, to the point it was noted down in detail by the medieval chronicler Saxo Grammaticus who described the Slavic pagan temple managed by the tribe of Rujani (an extinct West Slavic tribe, related to modern Poles). I’ll quote more about his description below at the end of this article.

Construction of the garlands is very precise and thoughtful, often being planned months before the harvest. Here’s one example of a technique used by some rural artisans nowadays:

Direct link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ntoKmSeWy9Y

Below you can see another video of preparations in the village of Lipnica Górna. At the beginning of the video the group sings an old folk song: ‘Naszą Matkę Ziemię trzeba nam szanować, byśmy jej plonami mogli się radować‘ (transl. ‘We have to respect our Mother Earth, so that we could rejoice with her yields‘):

Direct link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sDJppGPktjU

The garlands are placed on special platforms that often have to be carried by 4 people due to their overal weight. Nowadays, they can be also placed on a platform on wheels.

Smaller garlands were made by young women and girls, and later hung at homes.

In some regions of Poland these celebrations and the making of dożynki garlands were combined with the Day of the Divine Mother of Herbs.

PROCESSION WITH THE GARLAND

Dożynki were usually organized under a symbolic patronage of a local authority. In the pagan times, it might’ve been a chief of a clan, or an elder (sadly, no sources yet to confirm these theories clearly). Our only known sources date back to the long era of the folwark agricultural model (a serfdom-based farm and agricultural enterprise, usually large in size, that were operated in Poland from around the 14th century until around the beginning of 19th century, read also: serfdom in Poland).

The best-attested ethnographic resources we have date back to 19th century, already after the abolition of serfdom. During these times, the rural communities still cherished a custom of organizing a procession with the decorative garland to a local dwór (a rural manor house of Polish nobility = a local authority). Behind the garland, they carried also baskets with nuts and apples or other fruits and vegetables. Another important part of the ceremony was a bread baked from the fresh flour, made from the grains collected just recently from the fields.

People in the front of the procession were called przodownicy (derived from przodować – to lead, usually people of a certain position in the rural community or those who were rewarded for their hard work). They wore their best clothing, and had the honour of approaching the landowners with the goods they carried. Behind them went the whole community, carrying their tools such as sickles, and bouquets of flowers and herbs.

First, the procession went to a local church for blessing. Only then to the dwór. During the procession they sung songs in which the main recurring themes were the completed hard work on fields and the anticipation for upcoming feast with rewarding food and drinks. In many regions these dożynki songs were usually improvised, telling stories and recent news from the community, almost like a sung chronicle. These were among the most joyful celebration around the year. A lot of the songs had a humorous tone, and the people liked to tease the landlord by singing for example: “Mister, you chased us across the field with a stick, but bring us a bottle of vodka now / Mister, you chased us across the field with a lash, but let us in with this garland now” [M.Federowski].

The landlord waited for them on the porch of the dwór, and was given the fresh loaf of bread from the przodownicy (see also: traditional greeting with bread and salt), and given the garland. That part was adorned with ceremonial speeches during which the landlord thanked averyone for their hard work. Women among the przodownicy were then sometimes given a silver coin in return, and sprinkled with water (or their faces wiped with a wet cloth) in a ritual of evoking the fertility. The landlord personally carried the decorative garland inside the manor to put it in a honorary place, usually on the table in the main living room, and sometimes invited the przodownicy inside to share a shot of vodka.

The feast was usually organized close to the dwór, in the manorial yard where long tables and benches were prepared, or inside larger barns. The whole community was invited for a feast – unique celebrations when the peasants and the landlords sat and drank together. After that, young people went to a local karczma (inn or tavern) and danced until dawn.

The abolition of serfdom changed the structure of the rural communities. Already in the late 19th century more and more places of Poland hosted the dożynki simply by a local “gospodarz“, who could’ve been simply the richest peasant from a village. Each village had its own customs related to this tradition. Over the course of 19th- and 20th-century industrialization the custom eventually started dying out in many regions that no longer focused on agriculture.

Over time, the function of hosting dożynki got institutionalized. Already in the interwar period (period of Polish history between 1919-1939 when Poland was “reborn” as an independent state) there began a custom of organizing dożynki on administrative levels, hosted by either politicians or by local parishes, and the biggest dożynki were visited even by the president. After the World War 2, with the imposal of the communist regime and with the sudden decline of the nobility culture, the custom became even more political, inscribed into the communistic program of annual celebrations worshipping the hard work and the rural workers themselves. It carried on in a similar way until the modern day.

Nowadays, the dożynki festivals are organized by many agricultural-oriented gminy and powiaty (small and medium administrative levels of Poland), or even so-called “presidental dożynki” on a voivodeship level (the largest administrative levels of Poland, sometimes translated in English as provinces). Local politicians – mayors and presidents took the role of a “host”, and they became the model of authority who receives the garland and the bread and gives the speeches, often alongside the Catholic priests. Many of those gatherings took a form of a public festival with music on a central stage, food stalls, and mini amusement parks for children. Garlands are made for public contests.

Sadly, dożynki largely lost their mystical and ritual character. But the tradition in its simplified form is more or less still alive today.

HARVEST FESTIVAL FROM THE PAGAN ERA?

To finish this article, I’ll leave you with a quote describing an unnamed pagan festival celebrated by the Slavic tribe of Rujani who ran a temple dedicated to the god Svetovid, as noted down by the chronicler Saxo Grammaticus in 12th century. I’m putting it here without a further comment, and you can draw some analogies yourself:

Ceremonial services of [the cult of Svetovid] included: yearly, after counting results of the bountiful harvest, the island’s population crowded before the temple of the statue, cattle being sacrificed, and a ceremonial feast of the rites [devoted] to the divinity was celebrated. The priest [of the divinity], showing the strict observance of the length of hair and beard according to old traditions of the ancestral community; the day before [the feast] the priest had to perform an even more important service to the divinity; the temple, which only he had traditional right to enter, he used to clean most diligently with a broom, making sure he would not breath inside the temple; when he needed to breath in or out, he ran to the doors, to prevent pollution of the pure divine presence by the contact with mortal spirits.

The next day, the population [of the island], having gathered before the temple’s gates, was excited to see the horn taken out of the statue’s hand, [for] if the amount of the distilled mead [in the horn] was less than expected value, next year’s [crops] would be scarce. In that case, the current harvest would be prescribed to be conserved for the future. If the recessing of the usual fertility criterion was not seen, then the coming times of prolific crops was predicted. According to this prediction, either more economic or more liberal use of the yearly supply on-hand was prescribed. Then, after the old mead was poured out to the feet of the statute, as a libation to its divinity, [the priest] washed fresh the emptied horn, and, in similar obligatory toasts, having praised the statue and the people, in solemn oration proclaimed a wish of an annual increase of wealth and victory for [his] good fellow citizens. Having finished [the toasts], [the priest], closing the horn to [his] mouth, with huge, fast, consecutive gulps, drunk it out dry, [and] having replenished the honey drink [in the horn], re-deposited it into the right hand of the statue. A cake of round form, made with the use of honey, of such large size that [it] was almost equal to the human height, was brought forward as a sacrificial [gift]. Having placed the cake between him and the people, the priest would ask whether the Rugians could see him. To those who answered [that] they, from their position, could see him, he wished that the next year they would not be able to see him from there. These traditional sayings were related not to predictions of his of their fate, but to hopes of an increase of future harvest.

Then, [the priest], in the name of the deity of the statue, greeted the crowd, and for a long time encouraged them in conducting thorough sacrificial rituals to his divinity, and promised definite rewards for that in a form of victories on the ground and the sea. That finished, the rest of the day was protracted with the luxurious, plentiful feast, which could have turned the religious meal into [one of] joyous eating and gluttony, because [the abundance of] the sacrificed animals to the deity was provoking people to excesses. [If], in this moderate feast, someone was seen as violating restraint, [he] would be [considered] as breaking tradition.

(translated by Stanislaw Sielicki, corrector N. Christie, 2015)

Sources and references:

- Barbara Ogrodowska “Zwyczaje, obrzędy i tradycje w Polsce. Mały słownik. Wydanie II”, Warszawa 2001

- Józef Szczypka “Kalendarz polski”, Warszawa 1984

- “Saxo Grammaticus on Slavic Pre-Christian Religion. The Relevant Fragments from Book XIV of Gesta Danorum”, translated by Stanislaw Sielicki, corrector N. Christie, 2015

- Andrzej Szyjewski “Religia Słowian”, Kraków 2003

- Magdalena Kroh “Przemiany obrzędowości dorocznej we wsi Chyżówki“, in: Polska Sztuka Ludowa 1971 t.25 z.4; 231-250

- Michał Federowski ”Lud okolic Żarek, Siewierza i Pilicy. Jego zwyczaje, sposób życia, obrzędy, podania, gusła, zabobony, pieśni, zabawy, przysłowia, zagadki i właściwości mowy. Tom 1“, 1888-1889

- “Żniwa i dożynki”, article by Anna Stypuła on muzeum.lasochow.pl

Hello. I know you haven’t posted on this blog for a while, so I don’t know if you will see this comment. I had to write it anyways, in case you do.

I come from a mixed family. Half Belgian, half Polish. I was born in Belgium and speak the language, but I was never taught to read and write in Polish. I wanted to thank you for your hard work. Due to a fairly extreme religion, my family never kept any of the traditions you describe in your blog and I really feel like I missed out on so much.

Since I can’t read the language, work in English, like yours is very, very appreciated and I can learn so much to get in touch with my heritage. Thank you so much!

LikeLike